Hundreds of thousands of landmines strewn around areas near neighbouring countries pose a fatal risk to locals, but thanks to a concerted effort some headway is being made in clearing them

- Published: 27/05/2012

- Writer: Busaba Sivasomboon

- Bangkok Post

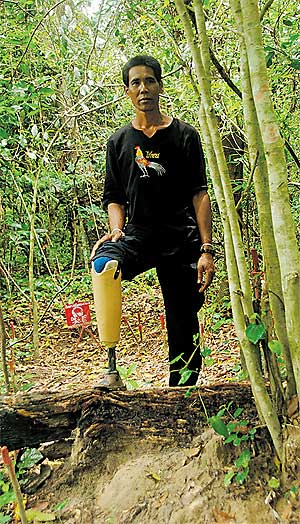

Chamroon Pengpit, 45, still vividly remembers the saddest day of his life _ the day he lost his leg.

FACING TRAUMA: Above, Chamroon Pengpit in front of the spot where he

stepped on a mine 24 years ago; Right, Mr Chamroon with his wife and a

nephew.

FACING TRAUMA: Above, Chamroon Pengpit in front of the spot where he

stepped on a mine 24 years ago; Right, Mr Chamroon with his wife and a

nephew.

It was early in the rainy season and he went with friends to pick

mushrooms that grew in the woods near the rugged border of Thailand and

Cambodia, close to his village. When he saw a wild Burmese grape, his

favourite fruit, he rushed to the tree unaware of the danger lurking in

the ground.

"I ran to the tree and ... kaboom! An immense force beneath my feet

threw me several metres away," he said. "I felt numb in the legs.

"I looked down and saw my right leg was badly shredded," he said, pointing to where his leg once was.

PHOTOS: BUSABA SIVASOMBOON

PHOTOS: BUSABA SIVASOMBOON

Mr Chamroon has been walking with a prosthesis for 24 years. His

disability hinders his productivity as a farmer and as a forest

scavenger, making it difficult for him to provide for his family.

The presence of landmines in neighbouring countries such as Laos,

Cambodia and Myanmar is well established, however thousands of Thais

have also suffered fates similar to that of Chamroon or worse.

Millions of landmines buried in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand

can be dated back to the Vietnam War era and later during the armed

conflicts in Cambodia. The war ended more than a decade ago but the

mines are still in the ground. There have also been allegations that

landmines were used in more recent border flare-ups.

Landmines are cheap _ about US$1-$30 (30-950 baht) apiece. They come

in a wide array of types such as anti-personnel and anti-tank, but all

have a common purpose _ to kill or injure the unsuspecting. The US State

Department estimates there are 60-70 million landmines buried around

the world's war-torn regions. The devices kill or maim about 25,000

people each year. In Thailand, up to 30 landmine casualties are reported

each year.

As well as killing people, landmines also hinder economic progress

and make the lives of residents very difficult. The presence of land

mines discourages the building of infrastructure and also hampers the

standard of living of locals, since they depend on the forests the same

way city-dwellers depend on supermarkets.

DEADLY SERIOUS LESSON: An official with Thailand Mine Action Centre

lectures schoolchildren in a landmine danger zone on the necessary

precautions they should take to avoid injury or death.

DEADLY SERIOUS LESSON: An official with Thailand Mine Action Centre

lectures schoolchildren in a landmine danger zone on the necessary

precautions they should take to avoid injury or death.

To clear them out is costly in terms of both of money and time. In

Thailand in the past the task of clearing mines was in the hands of the

military. In late 1998, Thailand was the first Southeast Asian country

to ratify the treaty to ban anti-personnel landmines, the Ottawa Treaty,

also known as the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention.

Under the treaty, Thailand was obliged to eradicate landmines within

10 years, but that deadline was extended another nine years after the

first period elapsed due to the slow progress of mine clearing. The

military-operated Thailand Mine Action Centre (TMAC) was set up under

the treaty to lead the mine clearing operations.

According to the Landmine Impact Survey, conducted from May 2000 to

June 2001, 933 distinct areas in 27 provinces were suspected of being

home to landmines and other unexploded ordnances. The total surface area

was estimated to be 2,557 square kilometres, More than 500,000 people

were found to have been affected in some manner by the presence of

landmines and ordnances, whether through personal injury or loss of

opportunity.

According to the TMAC, from 1999 to March 15 this year, 343,134 landmines were destroyed.

Most of the landmine-strewn areas are along the Thai-Cambodian

border, which can be partly attributed to the spillover from Cambodia

during its years of internal conflict. Additionally, many of the

landmines were the result of Thailand's conflict with its communist

insurgents.

Nobody knows exactly how many landmines remain in Thailand, though

officials Spectrum spoke to put the number at about one million.

Adding to the difficulty in estimating the number of landmines in

Thailand is the fact that a major area of conflict _ the western part of

the country _ remains out of the TMAC's purview.

The body has four demining units: two in southern Isan, one in Chanthaburi and one in the North.

TMAC officials believe Myanmar and ethnic minority groups are still

using mines in the western part of the country. But regular clashes make

it too dangerous for officials to work there and that means little

information is available on mines in the area.

Officials were tight-lipped when asked of allegations that Cambodians

have mined border areas as tensions between the two countries have

heightened due to the Preah Vihear dispute.

Locals were less circumspect, however, saying the number of mines and

related casualties has increased, particularly in routes commonly used

by people living in the area.

Mine clearer Charuwan Wannasri.

Mine clearer Charuwan Wannasri.

Earlier this month the Foreign Ministry directly accused Cambodia of

placing landmines along the Thai-Cambodian border after a Thai soldier

was badly wounded by one of the devices.

Sgt Chatree Kaewprasan of the 23rd Infantry Division was on foot

patrol near the disputed 4.6 sq km area near Preah Vihear temple when he

stepped on a landmine, which blew off his right leg. The army said at

the time that it suspected Cambodian loggers of having planted the mine,

owing to their frustrations over a Thai crackdown on log smuggling.

The flare-ups along the Thailand-Cambodia border have made the TMAC's work even harder.

Following its formation in 1998, the TMAC spent 10 years clearing out

mines using an old technique that has proven time-consuming and

resulted in little progress.

Using this method, mine clearers scan every square inch of areas

suspected of being home to mines, pull them out and later destroy them.

The thorough process ensures that the area is safe but the method is

time consuming and tedious.

''In that first decade, we were able to clear only three to five

square kilometres a year with the thorough clearance method. If we stuck

to that technique, we wouldn't be finished clearing landmines for

another 100 years,'' Lt Gen Chatree Changrien, TMAC's director-general,

said.

In 2010 the Norwegian People's Aid (NPA), an NGO, stepped in with a

new technique to speed up mine clearance. The organisation has been

involved in demining since 1992 and has helped to develop a technique

widely accepted internationally for its efficiency, called ''land

release''.

The land release method comprises three main activities.

The first is a non-technical survey which involves identifying a

suspected hazardous area and confirming whether the threat is genuine

and its extent.

The second step involves a technical survey of the area to confirm

the presence of the mines and to set about a detailed plan for their

clearance.

The final step involves the actual clearance, which can involve

manual equipment, mine detection animals such as rats and the use of

mine clearers.

''This technique is more efficient in terms of releasing far more

land to local people for their use and also faster than the old

technique,'' said Aksel Steen-Nilsen who is Thailand programme manager

for the NPA. ''We use a lot more information gathering from locals, then

analyse it before we move into the field. The land that we have

analysed and classified with low risk will be released to locals.''

By using this new method, the amount of land suspected to be mined in Thailand has decreased from 2,557 sq km to only 540 sq km.

Lt Gen Chatree expressed the hope that with the help of foreign NGOs,

including the NPA, more than 10 sq km of areas suspected to be mined

can be released this year.

If Thailand keeps up that pace it should be able to meet its deadline for landmine clearance in 2018.

The NPA, under the supervision of the TMAC, started its clearance

operations in Surin province on the Cambodian border in May of last year

with a civilian team of 10. The number has grown to 25 and they are

still active in mine clearing efforts in the area.

According to Mr Steen-Nilsen, the NPA is able to release 752,422

square metres in six months with the new technique. The NPA has also set

up a training course in which locals can enroll and become mine

clearers.

Charuwan Wannasri, 26, has been a mine clearer for NPS for one year.

She quit her retail job in a shopping mall in Bangkok and returned to

her hometown Surin to take care of her father who was seriously injured

in a car accident.

She didn't hesitate when the NPA started the programme, though she

knew the line of work is considered one of the world's most dangerous.

Many mine clearers have lost their lives during operations.

''I am not afraid of working close to explosives,'' she said. ''I think I'll be safe if I follow the instructions strictly.''

Besides a metal detector, a mine clearer's tools comprise a wooden

stick, a metal prodding stick, a paint brush and a red and white rope.

A wooden stick is used to detect trip wires and to clear vegetation

out of the area. A metal detector can then pinpoint mines. The dirt

around the bomb must be removed. The most dangerous procedure is

prodding with a metal stick to determine the exact point to excavate the

mine.

''I am proud of what I am doing. I can help so many people to live

without fear that someday they would be maimed or killed by bombs under

the ground,'' Ms Charuwan said.

Mr Chamroon is also excited to learn about the mine clearing efforts.

''Without those mines, villagers who depend on forest scavenging like

me would be able to earn more income because they can extend their

searches for things like mushrooms, wild vegetables and fruit, honey and

other things in the wood.''

Mr Chamroon's monthly income from his plantation is about 3,000 baht, far too little for him to support his family.

Though his three children have all grown up, married and live away

from him and his wife, he still has to feed his nephew who is living

with him.

''The forest is the best solution for our meagre income,'' he said.

''If I need anything other than rice, I just go to the forest and we can

find what we need. Landmines have made the lives of the poor who live

on the border more difficult. Without landmines, we could live happier

lives.

''I don't know why people have to create this kind of evil to kill

each other. And innocent people like us have to suffer from the remnants

of the wars that we did not take any part in,'' he said.

WHAT’S YOURS IS MINED: A team from Thailand Mine Action Centre in a cleared area next to an area which still needs demining.

WHAT’S YOURS IS MINED: A team from Thailand Mine Action Centre in a cleared area next to an area which still needs demining. EASY DOES IT : A mine clearer with Norwegian People’s Aid at

work.Below far right, a landmine is detonated. Above, various explosive

devices.

EASY DOES IT : A mine clearer with Norwegian People’s Aid at

work.Below far right, a landmine is detonated. Above, various explosive

devices.

2 comments:

You invade our motherland, you pay the price of losing yours limbs and lives. Karma!!

If you go to someone house you will get hurt or kill. Khmer has the right to defend their country land border.

We can planted and de-minded better than any Thai lady boys. We had much more experienced in killing our enemies than coward Siam, who depend on their big toys and be American's bitches.

Post a Comment