BY KRISTI EATON

Rong Ung bounds up the stairs to a classroom in a rickety building along a dirt road on the outskirts of Cambodia's capital of Phnom Penh, greeting the room full of young boys and girls in the Cambodian language of Khmer.

Over the next few hours, Ung, 26, teaches the kids a few English words and how to snap a photograph. At one point, he points out the swollen ankle of one of the girls, the result of a benign cut that got infected due to lack of medical care.

"When I first came here, it opened my eyes to everything. Why my parents were the way they were. Why they kept pushing me to focus on education," Ung, a Cambodian-American from Long Beach, California, now living in Cambodia, said. "I saw more the effects the families had - the PTSD, the suffering."

April 17th marks the 40th anniversary of the communist Khmer Rouge taking control of the country in its quest to become an agrarian society. Prior to the regime's rise to power, the United States was responsible for dropping 2.7 million tons of ordnance on Cambodia, killing and injuring hundreds of thousands of civilians. Some historians say this was a factor in the rise of the regime.

During and after the nearly four-year Khmer Rouge reign, several hundred thousand Cambodians fled, becoming refugees in faraway countries. In the U.S., many ended up in places like Long Beach, California, or Lowell, Massachusetts. Now, many of children of those who left are returning to their family's homeland, eager to learn about a country, culture and history that has shaped them since they were born.

Some, like Ung, never visited the country as a child. Nor did they initially have the support of their families in moving to the Southeast Asian country. Most of those returning are in their 20s or 30s, and unlike a wave of deportees sent back to Cambodia from the U.S. after getting caught up in gang or criminal activity, many of the latest returnees are college-educated, some having left promising careers in America to return to the country their parents left. They are educators, researchers, doctors, reporters and entrepreneurs with one thing in common: the desire to connect with the people in the country and help them improve their lives while also discovering more about themselves.

"The perception in the U.S. is that Cambodians don't care about one another," said Ung, who was a project manager at a non-governmental organization but now aims to start his own social enterprise that gives young people in the country a voice. "My whole purpose is working on spreading the news, to show Cambodians love Cambodians."

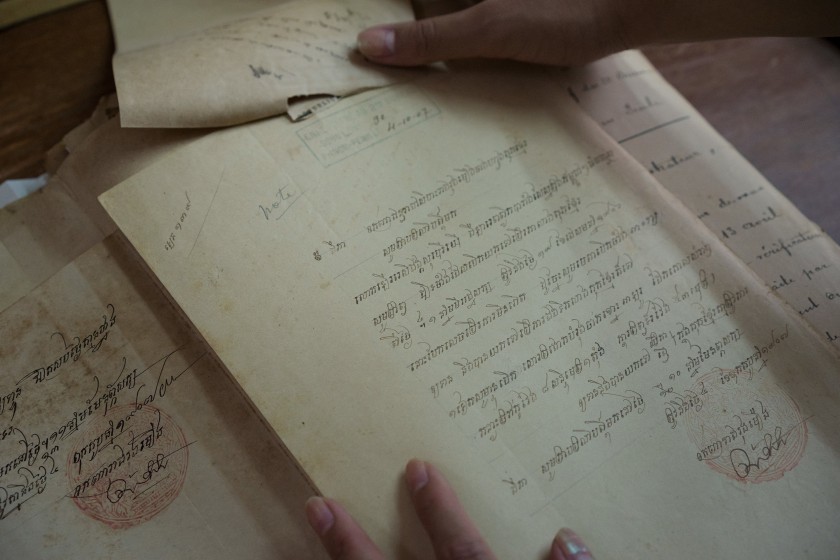

Cheryl Yin, 30, is studying hierarchies in the Khmer language and how it changed under the Khmer Rouge regime as a PhD candidate and graduate student in Linguistic Anthropology at the University of Michigan. Her parents, who identify as Chinese-Cambodian, immigrated to the U.S. during the Khmer Rouge era separately after spending time in Thai refugee camps.

"My parents were also very open with me about what happened to them during the Khmer Rouge, and so they told me how during the Khmer Rouge they tried to change the language," said Yin, who plans to spend a year or two pursuing her research. "They wanted everyone to be equal, so they changed the language to eliminate hierarchy."

Ung and Yin made conscious decisions to move to Cambodia, but others ended up living in the country after initially just planning to visit for a month or two. Born at a Thai refugee camp, Chanda Hun says she lost four siblings due to sickness and starvation. Despite that life-altering hardship, Hun found herself in Cambodia for what was supposed to be a short vacation. She ended up staying. That was six years ago.

Still, Hun says she often feels like she's stuck in between two different cultures: the fast food-eating, free-spirited American society, and the patriarchal, status-obsessed Cambodian society. "I'm not really American, but then I'm not really Cambodian," said the 34-year-old managing director of a hotel in Phnom Penh.

"Coming back, this feels like home"

Remy Hou was actually born in Cambodia but left for America in 1990 before returning last year. A fashion designer, Hou, 33, said it was important for him to manufacture from Cambodia, a country with a large garment industry, and not China. When protests broke out in 2013 and 2014 at the garment factories over wages and working conditions, leaving several people dead, Hou said he knew he needed to return and show that designers can make an impact.

"I wanted to come back home and have a product that was made in Cambodia because I am a Cambodian designer but an American designer, and I wanted to give back to my country as well," he said.

Despite spending the first part of his life in the country, Hou says he still stands out at times: he's relearning how to read and write the language as an adult and local vendors at the market will charge him the foreign rate. But he feels local in other ways. Now, when he goes out at night, he hears people speaking his native language.

Both Hou and Hun say Cambodia is a place where people can reinvent themselves and start over, and make a positive difference in the process using the education and skills they learned abroad.

"Coming back, this feels like home," Hou said.

For many of the returnees, there was a sense of shame about growing up Cambodian in the U.S. Nobody knew where the country was located or anything about its people, Ung says, and it represented everything he was working to avoid: violence, gang activity and a poor education. But once he started making trips to Cambodia in 2011, it opened his eyes to understanding how the country's past is affecting the present.

"I went in with the impression I was going to be teaching kids things like photography," he said. "But I was naive in the fact that they taught me so much more. They taught me how to love, how to truly care for something, how to live within my means, not want the best things. And as long as I have food, a loving family and a place to stay, that's all I need."

No comments:

Post a Comment