Driven by revenge, Youk Chhang (pictured) began documenting the horrors that befell

his people during the genocide in Cambodia. Now he's convinced his

country must confront its past to be able to shape its future.

Youk Chhang was 14 in 1975 when his life changed forever. A native of

Phnom Penh, he had learned to live with dread as the war raging in the

Cambodian countryside between the radical Khmer Rouge communists and

government forces got closer and closer to the capital. The sounds of

explosions outside the city had become commonplace; refugees streamed

into the city, seeking escape from the rural violence. Phnom Penh

residents, weary of years of war, just wanted peace, and quiet.

A sort of peace did descend, briefly, in April when Phnom Penh fell to

Khmer Rouge forces. Chhang was home alone since his mother and sister

had gone to a different part of the city looking for a safer place to

stay after a small rocket had landed near their home the day before.

They planned to come back for him when they found a refuge, but the road

was cut; they couldn't get back. On April 17, Chhang woke up to a very

unusual silence.

"All the sound I had heard for three or four years was gone," he said.

"I felt peaceful and I will never forget that feeling. But then suddenly

I began to hear footsteps coming close and then guns again."

Those approaching sounds were Khmer Rouge soldiers, who forced Chhang

and all the residents of the city to leave for the countryside, the

first step in the new regime's radical experiment to turn Cambodia into a

self-sufficient, agrarian utopia. The national nightmare had begun.

Bitter medicine

Chhang, separated from his family, would not see them again for months.

He was thrown into jail and would have been killed were it not for the

efforts of an older prisoner, who sacrificed his own life so the

teenager would have a future. His sister died after having her stomach

slashed open by guards; his mother had to stand by while he suffered

regular beatings, unable to do anything to protect her son.

Somehow, he and his mother survived, and Chhang even prospered, ending up at Yale University in the United States in the mid-1990s. There he began working with the Cambodian Genocide Program, a project that sought to find out as much as possible through scientific research about what had happened and who was responsible for the deaths of almost two million people, or about 21 percent of the population.

"Honestly, first I came to this research for revenge," Chhang said about

the anger that used to be his constant companion. It was fury that he

wasn't able to save his sister, fury that his mother still carried deep

scars from the period. "But through research and school I began to

change. The research helped me heal."

Documents of terror

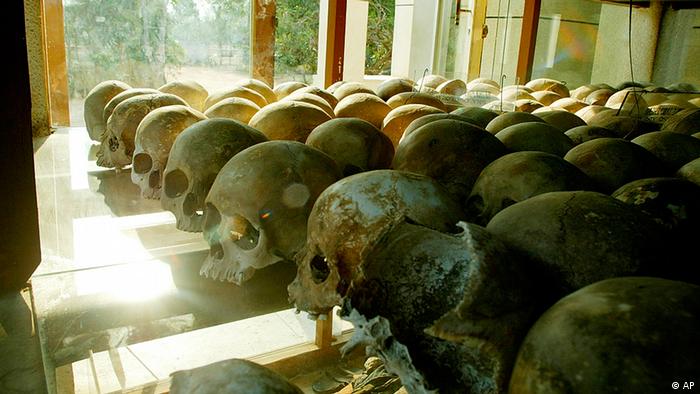

Today Chhang, 51, is the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which was born from the Yale program. Based in Phnom Penh, it is the world's biggest archive of Khmer Rouge material, with almost 160,000 pages of documents, 6,000 photographs and even sound recordings of revolutionary songs that were played to indoctrinate people or cover up the sounds of death in the killing fields.

Today Chhang, 51, is the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which was born from the Yale program. Based in Phnom Penh, it is the world's biggest archive of Khmer Rouge material, with almost 160,000 pages of documents, 6,000 photographs and even sound recordings of revolutionary songs that were played to indoctrinate people or cover up the sounds of death in the killing fields.

For Chhang such work is not easy. Like anyone who works closely

documenting human rights abuses, be they in Germany, Bosnia or Rwanda,

the research can take its toll. He says the hardest part of his job is

reading the personal letters written by parents to children, or husband

to wife, correspondence which was captured by Khmer Rouge guards. The

authors were almost invariably killed.

"It is so difficult to read how much people wanted to live knowing that

they would be executed the next minutes, but they still wrote," he said.

"That's difficult."

Still, he sees it as his mission to document what happened, and his

center organizes exhibitions and talks, helps people trace relatives

still missing. It also assists the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, which is trying

some of the movement's top leaders, and has written a textbook and

curriculum that are now mandatory in all the country's high schools.

Too scared to talk

Too scared to talk

Chhang says that many Cambodians still avoid talking about that time,

especially since so many Khmer Rouge soldiers and lower officials live

among the general population. But he thinks this reluctance to confront

the past directly hurts the country's development, making it difficult

for people to speak out, express their views and engage in the

democratic process. The fear is still deep seated, he says.

He talks about his mother, who took a different path than he did

regarding those horrible years in the 1970s. While he chose scientific

research as a tool to help him cope and even flourish, she retreated

into religion. And still, she does not like to talk about what happened.

It is still too painful. He, on the other hand, says talking about it

is the only way forward.

"Not everybody agrees with what I do," he said. "But through openness,

sincerity and honest research, I think that we can help shape the future

of this country."

1 comment:

This guy is a fake. Working for the CPP to cover up the real genocide and the Vietnamese invasion in Laos and Cambodia. Youk Chhang is paid millions by the US to cover up many crimes and many truth.

Post a Comment