Top: Ta Prohm temple near Siem Reap, Cambodia. Photograph: Souvik Bhattacharya/Getty Images/Flickr RF

Top: Ta Prohm temple near Siem Reap, Cambodia. Photograph: Souvik Bhattacharya/Getty Images/Flickr RF

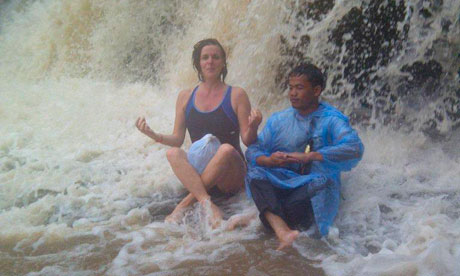

Middle: Kate in the waterfall Kate and guide Soriya in the River of a Thousand Lingas

Middle: Kate in the waterfall Kate and guide Soriya in the River of a Thousand LingasBottom: Ta Prohm, Cambodia Writer Crysse Morrison at Ta Prohm temple. Photograph: Stuart Kempster

On a Cambodian trip that paired self-reflection with full-on sightseeing, the lesson turned out to be one of going with the flow

By Kate Edgley

guardian.co.uk,

Friday 27 January 2012

I was on the top of Phnom Kulen, the most sacred mountain in Cambodia, in my cozzy in the pouring rain. I was teetering at the edge of the River of a Thousand Lingas, next to a wide waterfall, being splashed by a group of women pilgrims who were sitting in the holy water in their saris, laughing. That was when Soriya, our fully dressed guide, grabbed my hand and, pulling me along behind, waded in, picking his way along the boulders until we were up against the heavy rush of the waterfall. "One, two, three …" said Soriya and into the pounding downflow we went. We stood a moment in the small gap on the other side against the rock catching our breath before emerging to applause, clicking cameras and laughter from the pilgrims.

There were so many aspects to that scenario I would never have expected, an example of the Buddhist belief in letting go of expectations and living in the moment. I had gone to Cambodia – where 85% of the population is Buddhist – to join a group of western pilgrims on an "exploration path" amid the temples and jungles. It was a group holiday involving life therapy, led by humanist psychologist and leadership coach Michael Eales and author Crysse Morrison, a trip that, for me, turned out to provide several opportunities for letting go of expectations.

Cambodia, one of the poorest countries in south-east Asia after decades of war, is so undeveloped that the great temples built during the Angkorian era (from the ninth to the 15th centuries) are surrounded by jungle. A spot of inner exploration amid this magical setting was, I felt sure, on its way, from alternative holiday champions Skyros – for whom "life-changing" and "transforming" are common testimonials.

"All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveller is unaware," said Michael, quoting the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, and stoking my excitement for what lay ahead. A bus, for six long and bumpy hours the next morning, turned out to be the prosaic answer. And when we arrived in Battambang, a dip in the lovely rooftop pool of the Stung Sangke hotel (stungsangkehotel.com).

Our days began with the Skyros practice of demos (democracy), during which one of us would provide a thought for the day, and everyone was invited to express appreciation to someone or for something and to make suggestions for improvements. It kept the focus on what we were enjoying while providing a constructive way of dealing with niggles, and demonstrating that we – at least in our minds – create our own experiences.

Our experiences were many. The first excursion was to Phnom Sampeau, a hill with a dozen temples and much Khmer Rouge-induced bloodshed, 12km outside Battambang. Around 300 Cambodians died by being pushed off various parts of this steep outcrop, sometimes after having their throats slit first. A posse of children gathered around us as we climbed and then sat peering at our notebooks when we stopped to do a writing exercise, led by Crysse, who left her job as a lecturer and became a writer after a Skyros holiday 20 years ago. Afterwards we descended steps, the children sliding down the banister alongside us, into the Killing Cave, where a golden Buddha reclines alongside a glass memorial of skulls.

An energetic and uplifting Cirque du Soleil circus performance of skill and daring in Battambang that evening provided an entirely different kind of experience. The activities came thick and fast so I was glad when, after climbing 357 steps to Banon Temple, Michael introduced active listening, an exercise we performed in groups of four with each person talking uninterrupted about their thoughts and feelings while the other three listened. I sipped the juice from a coconut through a straw as we sat around a rickety table at a stall and each revealed a bit of ourselves.

The following day we were back in the bus and on to Siem Reap, via an archeological sight (which was closed), a sculptor (who was asleep) and a silk farm. The palatial 5-star Sokha Angkor (sokhahotels.com/siemreap), with a pool fed by pagoda-style waterfalls, was our luxurious home for the next four nights. Such magnificent quarters contrasted jarringly with the wooden shacks that most Cambodians call home, but the hotels we stayed in were at least locally owned, bringing desperately needed dollars into the economy.

Meals were mostly an array of shared stir-fried dishes, washed down with Angkor beer or French wine. Cheese and pastries are another legacy of France's colonial rule, but the food has a greater kinship with Thailand and Vietnam with servings of mixed vegetables – including the delicious morning glory (water spinach) – beef, or amok, the name a restaurant gives its own fish speciality.

Our first excursion from Siem Reap was the one everybody had been waiting for, to the magnificent Angkor Wat, the largest religious building in the world and a mind-blowing feat of engineering and devotion. To savour the moment that its spectacular western horizontal spread came into view, I had raced ahead of the group.

Unfortunately this meant I missed the explanation that we were, in fact, approaching from the opposite side and was confused and disappointed by my first sighting. Inside, humming with tourists, the trail took us around 800m of stunning bas-reliefs and past amazingly intact apsaras, or heavenly goddesses, carved into the stone. When I wasn't dodging the crowds, the sheer scale of the symmetry and the framed views of the jungle were breathtaking. There had been talk of lingering and writing but the bus was waiting to take us to lunch so I left Angkor Wat battling dissatisfaction with the fact that, like any other tourist, we had simply walked around it. We departed by the western approach so I waited until we were far enough away until I turned and there, in the centre of my vision … was green flapping tarpaulin! The secret destination of my Angkor Wat experience was, it seems, another lesson in expectation.

That evening, the haunting Ta Prohm, one of the temples just outside Siem Reap, where bizarre, monster-like spung trees and their roots have grown up, around and over the ruins, was blissfully tourist free.

Another moment of inner transportation came at Banteay Srei, the intricately carved women's temple, 30km from Siem Reap. As the day's light faded, we sat under a banyan tree in the grounds, where Michael began chanting with a powerful and haunting sound that the rest of us, sitting straight-backed and with our eyes closed, joined in. It lasted a few, perhaps five, minutes, and afterwards, as we walked away, I felt deeply peaceful and the jungle appeared suddenly vivid.

There was a visit to a well project, an apsara dance performance, and a rushed visit to Tuol Sleng, the prison where 17,000 were detained and tortured by the Khmer Rouge. It was a busy itinerary, involving many hours on the bus, which took in three of Cambodia's four main cities, temples galore and a good many sights beside. The journey, which began and ended in Phnom Penh, circumnavigated Tonlé Sap lake, the largest freshwater source in south-east Asia. It was a fascinating tour but lacked the stillness and reflection for the parallel internal journey that I had hoped for. Michael fed us thought-provoking quotes but the meditation, writing exercises and active listening came in snatched moments, providing an aside rather than underpinning an experience towards spiritual awakening.

"The mundane details of our life eat us up," said Michael, quoting Buddhist nun Ani Pema Chödrön. "Therefore it is important to keep asking ourselves again and again: what is the most important thing?" As it transpired, the most important thing was the outward journey, around a country of fascinating contrasts amid the remnants of one of the greatest empires the world has ever known. And as Cambodia emerges from centuries of invasion and poverty into the modern world, it was, perhaps, the perfect moment to visit. For that I feel grateful, which, as Buddhism teaches, is a very important step.

No comments:

Post a Comment