Special to the online edition of Windy City Times

by Camille Beredjick

18th January, 2012

Cambodian citizens, women especially, are taught not to question.

Critical thinking skills in school are overshadowed by emphasis on rote memorization. In 2007 the prime minister redefined "freedom of expression" to mean "freedom to say positive things about your government." Open expression is hardly visible in Cambodia, perhaps even barely existent.

However, in bits and pieces—in sharing information, collecting knowledge, reconsidering views once taken as facts—that can change.

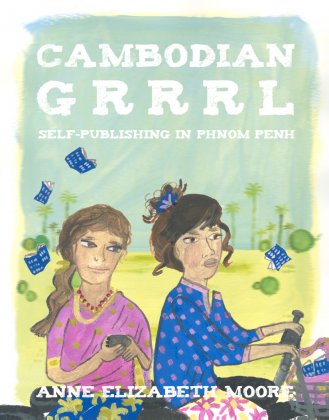

Anne Elizabeth Moore, a Chicago writer and artist, watched it happen. In 2007, she embarked on a project teaching young Cambodian women to think critically about their place in society through self-publishing. Four years and several trips later, her book Cambodian Grrrl: Self-Publishing in Phnom Penh, launched in September. The first in a series of four books and written as half-memoir/half-investigative journalism, Cambodian Grrrl is an account of teaching freedom of speech where it's least wanted.

"Realizing how deeply embedded notions of self-censorship and personal oppression and all these things were was pretty crazy," Moore said. "It's pretty unfathomable for Americans to even understand."

Cambodia's long, often brutal history has had a draining effect on its education system. After the reign of the violently oppressive Khmer Rouge ended in Cambodia in 1979, universities were not rebuilt until the 1990s. Years later, college-age Cambodian men were once again enrolling in college, but women were by and large staying out of school.

The problem was apparent: newly rebuilt Cambodian universities did not have dormitories, so students who lived out of town were out of luck. Men could rent apartments or stay in monasteries, but women are culturally prohibited from doing either. To overcome this hurdle and encourage Cambodian women to enroll, an American funder created a dormitory in Phnom Penh and selected 32 women from across the country to live there while attending college in the city.

Moore was invited to be a leadership resident in the dormitory, called the Euglossa Dormitory for University Women, and told she could work cooperatively on a project with the women. A self-publisher since her childhood, she decided they would work together to publish independent zines, or small, cheap, underground magazines.

Three times a week, she taught a self-publishing class that covered "zine construction, distribution, personal expression, graphic design, illustration and written English." The women created their own content and produced their own zines, which they distributed to locales throughout Phnom Penh.

It was a bold move in a country whose media is heavily government-controlled, where the nation's genocidal history was wiped from school curriculum as if to erase it from memory. Some zines explored the women's largely untold cultural history, though others were about boys, water buffalo and fun games to play. Either way, the zines were theirs.

"Figuring out how we could create our own political voice and actually put it out into the world in a safe way that wasn't going to get us in trouble is one thing," she said. "But realizing what the barriers to that were was a totally different thing."

One barrier was a simple book, a staple of Cambodian culture called the Chbap Srei, or Girl Law. The 19th-century book outlines women's place in Cambodian society based on very traditional restrictive cultural values. Unsurprisingly, its male-centered counterpart—Chbap Bros, or Boy Law—is much shorter.

Girl Law's guidelines range from taking care of babies and children in the room to staying quiet and still when your husband beats you. The young women Moore met were just beginning to study the book from a critical perspective, but its influence over their understanding of themselves was clear. In a later project, Moore and the women rewrote the book, calling the updated version New Girl Law.

"What I was able to see when I lived among this group of strong, independent, forward-thinking young women was that most of them still had copies of this book on their desks," Moore said. "Yes, they were studying them from a legal perspective and attempting to be critical of them, but the fact that it was still a day-to-day part of their culture was amazing."

By enforcing such aged constructs of gender, Cambodian culture likewise enforces heterosexuality. Moore said the young women she encountered considered it common sense that they should be married to men by the age of 24. The country is in the midst of a growing gay movement, Moore said, but the idea of any sexual relationship that defies heteronormativity is still shocking.

No comments:

Post a Comment