- January 24, 2013

- By: Colin Poitras

- http://today.uconn.edu

http://youtu.be/mtnliHX4M2Q

Scarred by years of torture and abuse under the brutal Khmer Rouge

regime, Cambodian refugees in the United States have been found to have

significantly higher physical and mental health problems compared to the

general population.

Helping them address their health issues and receive sustained,

adequate health care hasn’t been easy. Many of the refugees view Western

medicine as complementary to traditional Cambodian healing practices –

which may include Buddhist healers, herbalists, and acupuncture – and

only visit a primary care physician infrequently. Language barriers,

social isolation, lack of access to transportation, and limited

financial resources create further impediments to receiving quality

care.

In response to the problem, two UConn professors are working to

improve the health outcomes of Cambodian refugees through community

outreach, medication therapy management, innovative telemedicine and

technology services, research, and policy changes.

Thomas Buckley, an assistant clinical professor in the School of

Pharmacy and an expert on health disparities and access to care, has

been working with a Connecticut nonprofit advocacy group for the past

seven years to make sure older Cambodian-Americans in Connecticut,

Massachusetts, and California are taking the medications they need. In

addition to serving as a clinical consultant for Khmer Health Advocates

(KHA) of West Hartford – the only Cambodian-American health care

organization in the U.S. – he is preceptor of a clinical rotation for

UConn pharmacy students involving Cambodian refugees.

Megan

Berthold, assistant professor of social work, meets with Theanvy Kuoch,

executive director, right, Sengly Kong, co-investigator, left, and

Gabriel Babalola, financial manager, at Khmer Health Advocates in West

Hartford on Dec. 18, 2012. (Peter Morenus/UConn Photo)

On another front, S. Megan Berthold, assistant professor of social

work and an expert on the physical and mental health consequences of

trauma in refugee groups, has spent the past 12 years working with a

team of researchers to identify Cambodian refugee physical and mental

health problems through an NIMH-funded initiative undertaken in

collaboration with the RAND Corp. The project is led by Grant Marshall

of RAND Corp.

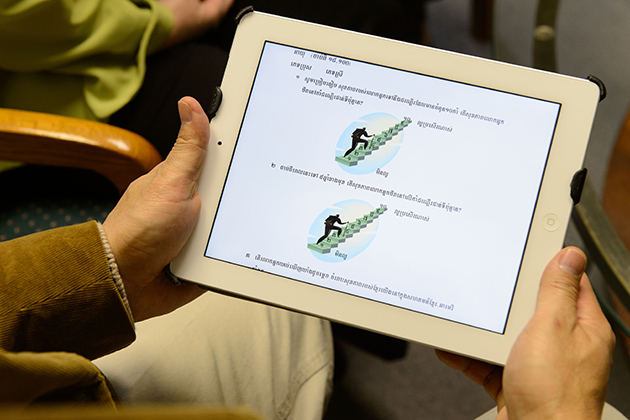

Berthold also recently started working with the KHA, where she

oversees a UConn-funded community-based participatory research study for

Cambodian-Americans that uses computer tablet technology and native

language software to assess the health needs of Cambodian-American

communities in six cities around the U.S.

Bridging the cultural gap

As part of the clinical rotation program Buckley manages at the KHA,

UConn pharmacy doctoral students work side-by-side with Cambodian

community outreach workers to assess the health needs of Cambodian

refugees and help them manage their medications. The students

participate in face-to-face visits with Cambodian-Americans in

Connecticut and Massachusetts, and help counsel individuals in

California through advanced video teleconferencing. Long Beach, Calif.

has the nation’s highest population of Cambodian-Americans, with more

than 70,000 residents.

“Cambodian-American health outcomes are especially bad because of the

treatment they received under the Khmer Rouge,” says Buckley. “Their

rates for diabetes, hypertension, depression, and other symptoms

associated with post-traumatic stress disorder are much higher than

other groups. Although the genocide of the Khmer Rouge happened 30 years

ago, the after-effect is still manifesting itself now.”

The UConn pharmacy students use a specially-developed questionnaire

to assess a person’s medication and health problems. The information is

then shared with a licensed pharmacist, who may recommend dosage

changes, alternate treatments, or other action. The students in the

program get first-hand experience with medication therapy management,

cultural competency training, and community pharmacy practices.

“We are exploring innovative ways pharmacists can work with a

community health worker and bridge the cultural gap in order to provide

better health services,” says Buckley.

“The biggest problem we see is the complexity of the therapies,” he

says. “A lot of people are getting their drugs from many different

sources. They don’t have one primary care physician controlling

everything. Because they have poor access to healthcare, they are

getting their drugs from a spouse, a sister, an uncle, a close friend …

we found people were taking multiple drugs that were doing the same

thing.”

Some of the nearly 100 Cambodian-Americans surveyed through the

program had stopped taking certain medications after experiencing

adverse side effects. Others took too much medicine, resulting in

additional health concerns.

As a result of the pharmacist-community worker intervention,

successful therapy outcome goals increased from 69 percent to 93 percent

among program participants over a 12-month period, inappropriate

medication use declined by 35 percent, and medication adherence improved

23 percent. A review of the program’s return on investment projected

that for every $1 associated with the cost of the program, $6 in health

care savings was returned.

Buckley’s work led to his receiving the Connecticut Pharmacists

Association’s 2012 Excellence in Innovation award for outstanding

advancement of pharmacy practice. He received the UConn Provost’s Award

for Excellence in Public Engagement in 2011.

Documenting physical and mental health problems

Berthold, meanwhile, recently entered the second phase of a major

research initiative involving the health and well-being of

Cambodian-Americans. She is part of a team of researchers at the RAND

Corp. that is documenting the prevalence of physical and mental health

problems among older Cambodian-Americans and examining whether there are

any links between trauma, post-traumatic stress reactions, and chronic

health problems.

Berthold says the longitudinal study with RAND has amassed a large

amount of data. “The U.S. Veterans’ Administration is very interested in

chronic health issues and the possible link between PTSD and depression

and chronic physical health problems such as cardiovascular problems,

high blood pressure, and diabetes. We are examining those issues in

Cambodian-American survivors of the Khmer Rouge Killing Fields.”

The RAND study was the first prevalence study of mental health

problems in a random sample of Cambodian-American survivors of the Khmer

Rouge genocide. Initial findings were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association

in 2005. As part of the second wave of research, Berthold is looking at

long-term mental and physical health issues in the sample population,

and, in a separate study, the mental and physical health of

Cambodian-American youth born in the U.S.

Building capacity

Berthold is also the principal investigator on a community-based

participatory research project in partnership with KHA and Cambodian

NGOs around the country. KHA project director SengLy Kong is

co-investigator. The study, funded by a UConn Faculty Large Grant,

involves testing the feasibility and effectiveness of training Cambodian

community health workers to collect data using iPad tablet computers.

The project aims to gauge Cambodian-Americans’ concerns about the

health of their communities, as well as their perceptions about barriers

to effective healthcare. Community members are able to interact with

the devices in their native Cambodian language Khmer. The results will

be interpreted by Cambodian-American community leaders around the

country who are partners on the project, and used by the community to

develop a comprehensive plan to reduce health disparities and improve

health outcomes in this population.

“Cambodian-American health outcomes are especially bad because of the treatment they received under the Khmer Rouge. … Although the genocide of the Khmer Rouge happened 30 years ago, the after-effect is still manifesting itself now.”

“We are trying to build capacity in the Cambodian-American community

across the country to conduct research and address the significant

health disparities they face,” says Berthold, who was named the National

Association of Social Workers 2009 Social Worker of the Year.

“Cambodian-American leaders from six states who run Cambodian-American

NGOs have collaborated as partners in the development and implementation

of every stage of this project. We plan to share the data through

telephone conference meetings, and ask for stakeholders’ help in

interpreting the data and identifying a focus for further research that

is meaningful and important to the Cambodian-American community.”

UConn experiential education field coordinator Lisa Bragaw and

associate clinical professor of pharmacy Devra Dang are assisting with

the research, as are UConn Health Center licensed clinical psychologists

Julie Wagner and Elizabeth Schilling, and Thiruchandurai Rajan,

professor of pathology and laboratory medicine.

Mary Scully, programs director for KHA and an advanced practice

registered nurse, says the work is greatly appreciated. “I think having

pharmacists more involved in health care is a very practical solution to

helping people with their medical problems,” she says. “The pharmacists

in our program have done a great job talking with the community. They

are very knowledgeable, and the community really picked up on that. They

loved the service and when they saw the drop in the depression rate, it

seemed to really empower them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment