PHNOM PENH, Cambodia — Moy Da hasn't seen his sister in nearly 40 years. Like countless Cambodian

families, they were separated during the reign of the Khmer Rouge. The

brutal communist regime made it official policy to dismantle the nuclear

family, which it considered a capitalist relic, and divided much of the

population into slave labor camps.

In 1975, Moy Da, then 5 years

old, and his parents, who died three years later, lost track of

15-year-old Pheap when the Khmer Rouge emptied Phnom Penh and marched

residents to the countryside. He has not seen her since, and the passage

of time has not dulled the pain. "Pol Pot took my sister from me," he

said. "I don't think I can go on living unless I see her again."

For

the first time in years, Moy Day has hope that they will be together

again, thanks to a groundbreaking reality TV show here. "It's Not a

Dream," which premiered in 2010, has reunited nearly two dozen families

separated during the Khmer Rouge days and the decades of civil war and

poverty that followed. Employing a team of young researchers who scour

the country for the missing, it brings together lost loved ones in

emotionally charged reunions filmed in front of a studio audience.

In the absence of Cambodian

institutions that perform this role, and in a country where neighboring

villages can seem worlds apart as a result of the enduring societal

fractures caused by the Khmer Rouge, the show is one of the few avenues

for Cambodians who hold out hope that missing relatives are still alive.

After

calling the show's hotline, Moy Da met with researchers in a windowless

room one recent afternoon in the bowels of Bayon TV, a popular network.

After compiling a dossier on his case, they would take it to local

authorities and broadcast it around the country on Bayon's television

and radio stations.

Nearly 60 people call the show's hotline every

day, and there are a half-dozen successful reunions waiting to be

filmed. Although there are no ratings services here, the show has

enthralled an audience of Khmer Rouge survivors, who make up about a

third of the population.

"Nearly every Cambodian family lost

someone. Our show gives them hope, and it allows viewers to go back to

their own story, to say to their children, 'See, this is what happened

to me,'" said producer Prak Sokhayouk, 30.

"It's Not a Dream" is one of a number of reality TV programs that examine social issues in Southeast Asia, including a Vietnamese show reuniting Vietnam War

families upon which it is based. Although steeped in the formal

conventions of their American counterparts — including a reliance on

voice-overs to construct narrative and music to trigger emotion — shows

such as "Every Singaporean Son" and Malaysia's "Young Imam" eschew cutthroat competition and fascination with celebrity in favor of investigations of family and religion.

In Cambodia, Korean soap operas dubbed in Khmer

and locally made karaoke videos are popular. Viewers outside the cities

watch these programs on communal TVs with rabbit ears powered by car

batteries. As a result, Cambodians are largely unfamiliar with "American

Idol" and "Jersey Shore,"

which prize extroversion and catharsis, leading to muted reactions

during the show's reunions. "Some people are shocked and don't know what

to do, and simply stand and look at each other," Prak Sokhayouk said.

Others are overcome with feeling but attempt to conceal this from the

camera, in keeping with a culture that frowns on outward displays of

emotion.

This creates challenges for Prak Sokhayouk, who must

strike a balance between the show's social purpose and her duty to

entertain the audience. She must also weigh concerns about privacy — if

one party does not want a reunion, the case is closed — and fears of

unleashing dormant trauma among survivors of extreme hardship. (The show

does not employ psychologists, who number less than one for every

200,000 people in a country where PTSD is widespread.)

Eng

Kok-Thay, director of research at the Documentation Center of Cambodia,

which investigates Khmer Rouge crimes, said the show helps create a

national discussion about the missing. He estimates that 50% of

Cambodian families were separated by the regime, which reorganized a

society structured principally around family into one built almost

exclusively for labor. Children as young as 5 were forced to leave their

parents and join work crews. "It was easier to control people if they

were separated. The Khmer Rouge became their family," Eng Kok-Thay said.

After

the defeat of Pol Pot's forces by the Vietnamese in 1979, survivors

returned to their home villages and neighborhoods in search of

relatives. Many were successful, but grinding poverty and 20 further

years of civil war with remnants of the Khmer Rouge created new

separations.

"It's Not a Dream" helps these families too. On an

evening in September, Heng Vicheka, 25, sat on a Bayon soundstage and

described, in a voice ragged with sorrow, how he lost his family in

1993. They had lived in Banteay Meanchey, a remote northwestern province

that was a stronghold of Khmer Rouge guerrillas, when he wandered off

one day and couldn't find his way back home. What followed — a

procession of orphanages and odd jobs, punctuated by physical abuse —

left him desperately poor and unmoored.

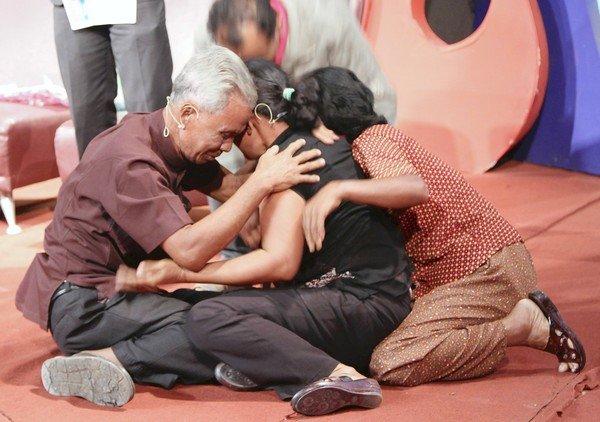

After a series of video

montages described his circumstances, the moment finally came when his

mother and father joined him on stage. Overwhelmed, Heng Vicheka removed

his sandals, a sign of respect, and fell into their arms, his back to

the audience. His mother, Phorn Sopheap, sobbed softly and said, "I

never thought I would see you again." She vowed to shave her head to

give thanks to the gods that reunited them. Many in the audience wept

silently.

Backstage, as Heng Vicheka's father straightened his

son's shirt collar for their first family photo in two decades, his

mother talked about their future. "I don't know what happens next. It's

up to my son. If he wants to live with us, we will," she said. She

paused for a moment and smiled. "But first, I will take my son home to

see his family."

No comments:

Post a Comment