October 26, 2009

By Traci Scott,

By Traci Scott,

Oregon faith Reporter,

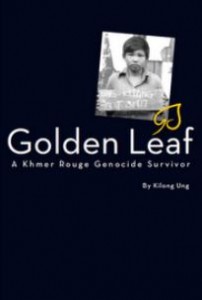

As conveyed in his recent book, “Golden Leaf: a Khmer Rouge Genocide Survivor”, Kilong Ung was a “golden leaf” propelled by the wind that blew him from one terrifying part of the world to the next. Through adverse weather, turmoil and calamity, he was subjected to a barrage of horrors. While two million other leaves disintegrated along the way, Ung persevered against all odds, rose above the devastation, and landed safely here in Oregon. His legacy is the tree that took root and the many branches he has utilized to reach out to others who have experienced a similar plight.

For more than 30 years, Kilong Ung, currently a Portland software engineer, struggled with nightmares, insomnia, paranoia and haunting memories of nearly starving to death in a slave labor camp where his parents and other family members perished before his very eyes.

Ung was living in the city of Battambang in Northwest Cambodia with his parents and seven sisters in 1975 when the brutal Khmer Rouge regime took control of the country. During its four years in power, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, attempted to completely recreate Cambodian society by systematically imprisoning, torturing, starving and executing nearly two million people, primarily those considered urban and intellectual.

Wweek.com recounts how the Khmer Rouge invaded Ung’s town and forced his family into slave labor camps where they worked 13 hours a day. Daily rations were two small bowls of rice porridge, plus whatever wildlife they could catch on their own. Although his mother grew weak, she refused to eat the rats he caught.

“To some people, they would rather die than go that route. My mother was one of those,” Ung told wweek.com. “Eating rats—if you get to that point, you’re pretty much dead anyway. You’re no longer human.”

In addition to losing his mother and father, Ung lost his youngest sister and seven other relatives to exhaustion, starvation, and disease. Other Cambodians were subject to torture and execution across the country’s infamous “killing fields”.

The Vietnamese overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, and Ung fled to Thailand with his older sister and her boyfriend, according to wweek.com. The three came to America as refugees and eventually settled in Portland. Ung graduated from Cleveland High School and Reed College, where he earned a math degree.

Ung went on to graduate school and several well-paid jobs in the corporate world. Along the way, he married his high school sweetheart, Lisa, and together they had two children. But the nightmares continued, despite his successes.

Ung hoped to find a way to share his experiences with his two children, as well as honoring the survivors and non-survivors of the atrocities. He decided to write a book to achieve both objectives. This summer, he self-published his memoir and is hoping his book will help to heal the wounds that continue to plague his homeland.

The book depicts the cruel, agonizing and ravenous life inside a labor camp from a survivor’s perspective. He describes burying his grandmother, his frantic attempt to catch and eat a rat and his degrading arrest for stealing a coconut, among other painful and horrific experiences.

“On the one hand, I wanted to free myself from this memory. On the other hand, I was afraid to lose that memory,” Ung told wweek.com. “Anything I put down in the book, I am clear from it now…. and my nightmares are better.”

According to The Oregonian, Ung hopes his memoir will “leverage the past” and help his native country. He plans to use some of the proceeds from the sale of the book to build a school in Cambodia, which he plans to name “Golden Leaf.”

Ung also hopes to encourage others in the Cambodian community through his leadership and involvement as a language teacher, youth mentor and past president of the Cambodian American Community of Oregon (CACO), which provides support for members of the Cambodian community. His aspires to serve as a bridge between the Cambodian and American communities and hopes his successes will inspire and motivate others.

Mardine Mao, current president of the CACO, told The Oregonian that what sets Ung apart from fellow survivors is his ability to transform pain and suffering into something positive. “His work is a great example that ordinary people can do extraordinary things. It provides an inspiration to those of us that may want to share similar stories,”

“I’ve lost so much,” Ung told The Oregonian, “and if I do nothing with the past, all that has happened would have happened for nothing. A book becomes evidence. It becomes a legacy, a document.”

Ung is a living testament to the power of faith and forgiveness—that through these virtues one can rise above life’s seemingly insurmountable challenges and not only survive, but thrive.

For more than 30 years, Kilong Ung, currently a Portland software engineer, struggled with nightmares, insomnia, paranoia and haunting memories of nearly starving to death in a slave labor camp where his parents and other family members perished before his very eyes.

Ung was living in the city of Battambang in Northwest Cambodia with his parents and seven sisters in 1975 when the brutal Khmer Rouge regime took control of the country. During its four years in power, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, attempted to completely recreate Cambodian society by systematically imprisoning, torturing, starving and executing nearly two million people, primarily those considered urban and intellectual.

Wweek.com recounts how the Khmer Rouge invaded Ung’s town and forced his family into slave labor camps where they worked 13 hours a day. Daily rations were two small bowls of rice porridge, plus whatever wildlife they could catch on their own. Although his mother grew weak, she refused to eat the rats he caught.

“To some people, they would rather die than go that route. My mother was one of those,” Ung told wweek.com. “Eating rats—if you get to that point, you’re pretty much dead anyway. You’re no longer human.”

In addition to losing his mother and father, Ung lost his youngest sister and seven other relatives to exhaustion, starvation, and disease. Other Cambodians were subject to torture and execution across the country’s infamous “killing fields”.

The Vietnamese overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, and Ung fled to Thailand with his older sister and her boyfriend, according to wweek.com. The three came to America as refugees and eventually settled in Portland. Ung graduated from Cleveland High School and Reed College, where he earned a math degree.

Ung went on to graduate school and several well-paid jobs in the corporate world. Along the way, he married his high school sweetheart, Lisa, and together they had two children. But the nightmares continued, despite his successes.

Ung hoped to find a way to share his experiences with his two children, as well as honoring the survivors and non-survivors of the atrocities. He decided to write a book to achieve both objectives. This summer, he self-published his memoir and is hoping his book will help to heal the wounds that continue to plague his homeland.

The book depicts the cruel, agonizing and ravenous life inside a labor camp from a survivor’s perspective. He describes burying his grandmother, his frantic attempt to catch and eat a rat and his degrading arrest for stealing a coconut, among other painful and horrific experiences.

“On the one hand, I wanted to free myself from this memory. On the other hand, I was afraid to lose that memory,” Ung told wweek.com. “Anything I put down in the book, I am clear from it now…. and my nightmares are better.”

According to The Oregonian, Ung hopes his memoir will “leverage the past” and help his native country. He plans to use some of the proceeds from the sale of the book to build a school in Cambodia, which he plans to name “Golden Leaf.”

Ung also hopes to encourage others in the Cambodian community through his leadership and involvement as a language teacher, youth mentor and past president of the Cambodian American Community of Oregon (CACO), which provides support for members of the Cambodian community. His aspires to serve as a bridge between the Cambodian and American communities and hopes his successes will inspire and motivate others.

Mardine Mao, current president of the CACO, told The Oregonian that what sets Ung apart from fellow survivors is his ability to transform pain and suffering into something positive. “His work is a great example that ordinary people can do extraordinary things. It provides an inspiration to those of us that may want to share similar stories,”

“I’ve lost so much,” Ung told The Oregonian, “and if I do nothing with the past, all that has happened would have happened for nothing. A book becomes evidence. It becomes a legacy, a document.”

Ung is a living testament to the power of faith and forgiveness—that through these virtues one can rise above life’s seemingly insurmountable challenges and not only survive, but thrive.

No comments:

Post a Comment